Chữ ký số

Chữ ký số là một tập con của chữ ký điện tử. Ta có thể dùng định nghĩa về chữ ký điện tử cho chữ ký số:

Chữ ký điện tử là thông tin đi kèm theo dữ liệu (văn bản, hình ảnh, video…) nhằm mục đích xác định người chủ của dữ liệu đó[5].

Ta cũng có thể sử dụng định nghĩa rộng hơn, bao hàm cả mã nhận thực, hàm băm và các thiết bị bút điện tử.

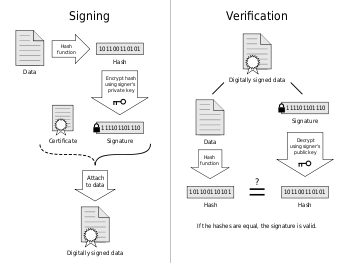

Chữ ký số khóa công khai (hay hạ tầng khóa công khai) là mô hình sử dụng các kỹ thuật mật mã để gắn với mỗi người sử dụng một cặp khóa công khai – bí mật và qua đó có thể ký các văn bản điện tử cũng như trao đổi các thông tin mật. Khóa công khai thường được phân phối thông qua chứng thực khóa công khai. Quá trình sử dụng chữ ký số bao gồm 2 quá trình: tạo chữ ký và kiểm tra chữ ký.

Chữ ký số khóa công khai (hay hạ tầng khóa công khai) là mô hình sử dụng các kỹ thuật mật mã để gắn với mỗi người sử dụng một cặp khóa công khai – bí mật và qua đó có thể ký các văn bản điện tử cũng như trao đổi các thông tin mật. Khóa công khai thường được phân phối thông qua chứng thực khóa công khai. Quá trình sử dụng chữ ký số bao gồm 2 quá trình: tạo chữ ký và kiểm tra chữ ký.

Khái niệm chữ ký điện tử – mặc dù thường được sử dụng cùng nghĩa với chữ ký số nhưng thực sự có nghĩa rộng hơn. Chữ ký điện tử chỉ đến bất kỳ phương pháp nào (không nhất thiết là mật mã) để xác định người chủ của văn bản điện tử. Chữ ký điện tử bao gồm cả địa chỉ telex và chữ ký trên giấy được truyền bằng fax.

Lịch sử

Con người đã sử dụng các hợp đồng dưới dạng điện tử từ hơn 100 năm nay với việc sử dụng mã Morse và điện tín. Vào năm 1889, tòa án tối cao bang New Hampshire (Hoa kỳ) đã phê chuẩn tính hiệu lực của chữ ký điện tử. Tuy nhiên, chỉ với những phát triển của khoa học kỹ thuật gần đây thì chữ ký điện tử mới đi vào cuộc sống một cách rộng rãi [6].

Vào thập kỷ 1980, các công ty và một số cá nhân bắt đầu sử dụng máy fax để truyền đi các tài liệu quan trọng. Mặc dù chữ ký trên các tài liệu này vẫn thể hiện trên giấy nhưng quá trình truyền và nhận chúng hoàn toàn dựa trên tín hiệu điện tử.

Hiện nay, chữ ký điện tử có thể bao hàm các cam kết gửi bằng email, nhập các số định dạng cá nhân (PIN) vào các máy ATM, ký bằng bút điện tử với thiết bị màn hình cảm ứng tại các quầy tính tiền[7], chấp nhận các điều khoản người dùng (EULA) khi cài đặt phần mềm máy tính, ký các hợp đồng điện tử online[8]… (vui long trich nguan khi copy tu day valeking132@yahoo.com.vn)

Các ưu điểm của chữ ký số

Việc sử dụng chữ ký số mang lại một số lợi điểm sau:

Khả năng xác định nguồn gốc

Các hệ thống mật mã hóa khóa công khai cho phép mật mã hóa văn bản với khóa bí mật mà chỉ có người chủ của khóa biết. Để sử dụng chữ ký số thì văn bản cần phải được mã hóa bằng hàm băm (văn bản được “băm” ra thành chuỗi, thường có độ dài cố định và ngắn hơn văn bản) sau đó dùng khóa bí mật của người chủ khóa để mã hóa, khi đó ta được chữ ký số. Khi cần kiểm tra, bên nhận giải mã (với khóa công khai) để lấy lại chuỗi gốc (được sinh ra qua hàm băm ban đầu) và kiểm tra với hàm băm của văn bản nhận được. Nếu 2 giá trị (chuỗi) này khớp nhau thì bên nhận có thể tin tưởng rằng văn bản xuất phát từ người sở hữu khóa bí mật. Tất nhiên là chúng ta không thể đảm bảo 100% là văn bản không bị giả mạo vì hệ thống vẫn có thể bị phá vỡ.

Vấn đề nhận thực đặc biệt quan trọng đối với các giao dịch tài chính. Chẳng hạn một chi nhánh ngân hàng gửi một gói tin về trung tâm dưới dạng (a,b), trong đó a là số tài khoản và b là số tiền chuyển vào tài khoản đó. Một kẻ lừa đảo có thể gửi một số tiền nào đó để lấy nội dung gói tin và truyền lại gói tin thu được nhiều lần để thu lợi (tấn công truyền lại gói tin).

Tính toàn vẹn

Cả hai bên tham gia vào quá trình thông tin đều có thể tin tưởng là văn bản không bị sửa đổi trong khi truyền vì nếu văn bản bị thay đổi thì hàm băm cũng sẽ thay đổi và lập tức bị phát hiện. Quá trình mã hóa sẽ ẩn nội dung của gói tin đối với bên thứ 3 nhưng không ngăn cản được việc thay đổi nội dung của nó. Một ví dụ cho trường hợp này là tấn công đồng hình (homomorphism attack): tiếp tục ví dụ như ở trên, một kẻ lừa đảo gửi 1.000.000 đồng vào tài khoản của a, chặn gói tin (a,b) mà chi nhánh gửi về trung tâm rồi gửi gói tin (a,b3) thay thế để lập tức trở thành triệu phú!Nhưng đó là vấn đề bảo mật của chi nhánh đối với trung tâm ngân hàng không hẳn liên quan đến tính toàn vẹn của thông tin gửi từ người gửi tới chi nhánh, bởi thông tin đã được băm và mã hóa để gửi đến đúng đích của nó tức chi nhánh, vấn đề còn lại vấn đề bảo mật của chi nhánh tới trung tâm của nó

Tính không thể phủ nhận

Trong giao dịch, một bên có thể từ chối nhận một văn bản nào đó là do mình gửi. Để ngăn ngừa khả năng này, bên nhận có thể yêu cầu bên gửi phải gửi kèm chữ ký số với văn bản. Khi có tranh chấp, bên nhận sẽ dùng chữ ký này như một chứng cứ để bên thứ ba giải quyết. Tuy nhiên, khóa bí mật vẫn có thể bị lộ và tính không thể phủ nhận cũng không thể đạt được hoàn toàn.

Thực hiện chữ ký số khóa công khai

Chữ ký số khóa công khai dựa trên nền tảng mật mã hóa khóa công khai. Để có thể trao đổi thông tin trong môi trường này, mỗi người sử dụng có một cặp khóa: một công khai và một bí mật. Khóa công khai được công bố rộng rãi còn khóa bí mật phải được giữ kín và không thể tìm được khóa bí mật nếu chỉ biết khóa công khai.

Sơ đồ tạo và kiểm tra chữ ký số

Toàn bộ quá trình gồm 3 thuật toán:

* Thuật toán tạo khóa

* Thuật toán tạo chữ ký số

* Thuật toán kiểm tra chữ ký số

Xét ví dụ sau: Bob muốn gửi thông tin cho Alice và muốn Alice biết thông tin đó thực sự do chính Bob gửi. Bob gửi cho Alice bản tin kèm với chữ ký số. Chữ ký này được tạo ra với khóa bí mật của Bob. Khi nhận được bản tin, Alice kiểm tra sự thống nhất giữa bản tin và chữ ký bằng thuật toán kiểm tra sử dụng khóa công cộng của Bob. Bản chất của thuật toán tạo chữ ký đảm bảo nếu chỉ cho trước bản tin, rất khó (gần như không thể) tạo ra được chữ ký của Bob nếu không biết khóa bí mật của Bob. Nếu phép thử cho kết quả đúng thì Alice có thể tin tưởng rằng bản tin thực sự do Bob gửi.

Thông thường, Bob không mật mã hóa toàn bộ bản tin với khóa bí mật mà chỉ thực hiện với giá trị băm của bản tin đó. Điều này khiến việc ký trở nên đơn giản hơn và chữ ký ngắn hơn. Tuy nhiên nó cũng làm nảy sinh vấn đề khi 2 bản tin khác nhau lại cho ra cùng một giá trị băm. Đây là điều có thể xảy ra mặc dù xác suất rất thấp.

Một vài thuật toán chữ ký số

* Full Domain Hash, RSA-PSS …, dựa trên RSA

* DSA

* ECDSA

* ElGamal signature scheme

* Undeniable signature

* SHA (thông thường là SHA-1) với RSA

Tình trạng hiện tại – luật pháp và thực tế

Tất cả các mô hình chữ ký số cần phải đạt được một số yêu cầu để có thể được chấp nhận trong thực tế:

* Chất lượng của thuật toán: một số thuật toán không đảm bảo an toàn;

* Chất lượng của phần mềm/phần cứng thực hiện thuật toán;

* Khóa bí mật phải được giữ an toàn;

* Quá trình phân phối khóa công cộng phải đảm bảo mối liên hệ giữa khóa và thực thể sở hữu khóa là chính xác. Việc này thường được thực hiện bởi hạ tầng khóa công cộng (PKI) và mối liên hệ khóa\leftrightarrowngười sở hữu được chứng thực bởi những người điều hành PKI. Đối với hệ thống PKI mở, nơi mà tất cả mọi người đều có thể yêu cầu sự chứng thực trên thì khả năng sai sót là rất thấp. Tuy nhiên các PKI thương mại cũng đã gặp phải nhiều vấn đề có thể dẫn đến những văn bản bị ký sai.

* Những người sử dụng (và phần mềm) phải thực hiện các quá trình đúng thủ tục (giao thức).

Chỉ khi tất cả các điều kiện trên được thỏa mãn thì chữ ký số mới là bằng chứng xác định người chủ (hoặc người có thẩm quyền) của văn bản.

Một số cơ quan lập pháp, dưới sự tác động của các doanh nghiệp hy vọng thu lợi từ PKI hoặc với mong muốn là người đi tiên phong trong lĩnh vực mới, đã ban hành các điều luật cho phép, xác nhận hay khuyến khích việc sử dụng chữ ký số. Nơi đầu tiên thực hiện việc này là bang Utah (Hoa kỳ). Tiếp theo sau là các bang Massachusetts và California. Các nước khác cũng thông qua những đạo luật và quy định và cả Liên hợp quốc cũng có những dự án đưa ra những bộ luật mẫu trong vấn đề này. Tuy nhiên, các quy định này lại thay đổi theo từng nước tùy theo điều kiện về trình độ khoa học (mật mã học). Chính sự khác nhau này làm bối rối những người sử dụng tiềm năng, gây khó khăn cho việc kết nối giữa các quốc gia và do đó làm chậm lại tiến trình phổ biến chữ ký số.

Khía cạnh pháp luật

Một số quy định liên quan tới giá trị pháp lý của chữ ký số:

Trung quốc

* Luật chữ ký điện tử của Trung quốc (tiếng Trung quốc) – Mục tiêu hướng tới thống nhất việc thực hiện, khẳng định tính pháp lý và bảo vệ quyền lợi hợp pháp của các bên liên quan tới việc thực hiện chữ ký điện tử.

Brazil

* Medida provisória 2.200-2 (tiếng Bồ đào nha) – Luật Brazil thừa nhận tính pháp lý của văn bản số nếu được chứng nhận bởi ICP-Brasil (PKI chính thức của Brazil) hoặc một PKI khác nếu các bên đồng ý.

Liên hiệp châu Âu

* EU đã thiết lập khung pháp lý cho chữ ký điện tử:

o Hướng dẫn số 1999/93/EC của Quốc hội châu Âul ngày 13 tháng 12 năm 1999 về khung pháp lý của chữ ký điện tử.

o Quyết định 2003/511/EC sử dụng 3 thỏa thuận tại hội thảo CEN làm tiêu chuẩn kỹ thuật.

* Các luật ban hành: Một số quốc gia đã thực hiện quyết định 1999/93/EC.

o Áo

+ Luật chữ ký, 2000

o Anh, Scotland và Wales

+ Luật thông tin điện tử, 2000

o Đức

+ Luật chữ ký, 2001

o Lithuania

+ Luật chữ ký điện tử, 2002

o Nauy

+ Luật chữ ký điện tử, 2001 (tiếng Nauy).

o Tây ban nha

+ Ley 59/2003, de 19 de diciembre, de firma electrónica (tiếng Tây ban nha).

o Thụy điển

+ Qualified Electronic Signatures Act (SFS 2000:832) (tiếng Thụy điển).

+ SFS 2000:832 bản dịch tiếng Anh

Ấn độ

* Luật Công nghệ thông tin, 2000

New Zealand

* Luật Giao dịch điện tử, 2003 điều 22-24

Luật thương mại quốc tế của Ủy ban Liên hiệp quốc

* UNCITRAL Luật mẫu về chữ ký điện tử (2001), bộ luật có ảnh hưởng lớn.

Hoa kỳ

* Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA)

* Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (E-SIGN), at 15 U.S.C. 7001 et seq.

Thụy sỹ

* Luật liên bang về dịch vụ chứng thực liên quan tới chữ ký điện tử, 2003

Uruguay

Luật pháp Uruguay bao gồm cả chữ ký điện tử và chữ ký số:

* Liên quan tới mật khẩu và các hành động tương đương trong công nghệ thông tin

* Liên quan tới chữ ký số, chữ ký điện tử và PKI

Việt Nam

* Luật Giao dịch điện tử[9][10] – có hiệu lực từ ngày 1 tháng 3 năm 2006.

Digital signature

A digital signature or digital signature scheme is a mathematical scheme for demonstrating the authenticity of a digital message or document. A valid digital signature gives a recipient reason to believe that the message was created by a known sender, and that it was not altered in transit. Digital signatures are commonly used for software distribution, financial transactions, and in other cases where it is important to detect forgery or tampering.

Digital signatures are often used to implement electronic signatures, a broader term that refers to any electronic data that carries the intent of a signature,[1] but not all electronic signatures use digital signatures.[2][3][4] In some countries, including the United States, India, and members of the European Union, electronic signatures have legal significance. However, laws concerning electronic signatures do not always make clear whether they are digital cryptographic signatures in the sense used here, leaving the legal definition, and so their importance, somewhat confused.

Digital signatures employ a type of asymmetric cryptography. For messages sent through a nonsecure channel, a properly implemented digital signature gives the receiver reason to believe the message was sent by the claimed sender. Digital signatures are equivalent to traditional handwritten signatures in many respects; properly implemented digital signatures are more difficult to forge than the handwritten type. Digital signature schemes in the sense used here are cryptographically based, and must be implemented properly to be effective. Digital signatures can also provide non-repudiation, meaning that the signer cannot successfully claim they did not sign a message, while also claiming their private key remains secret; further, some non-repudiation schemes offer a time stamp for the digital signature, so that even if the private key is exposed, the signature is valid nonetheless. Digitally signed messages may be anything representable as a bitstring: examples include electronic mail, contracts, or a message sent via some other cryptographic protocol.

Definition

A digital signature scheme typically consists of three algorithms:

* A key generation algorithm that selects a private key uniformly at random from a set of possible private keys. The algorithm outputs the private key and a corresponding public key.

* A signing algorithm that, given a message and a private key, produces a signature.

* A signature verifying algorithm that, given a message, public key and a signature, either accepts or rejects the message’s claim to authenticity.

Two main properties are required. First, a signature generated from a fixed message and fixed private key should verify the authenticity of that message by using the corresponding public key. Secondly, it should be computationally infeasible to generate a valid signature for a party who does not possess the private key.

History

In 1976, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman first described the notion of a digital signature scheme, although they only conjectured that such schemes existed.[5][6] Soon afterwards, Ronald Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Len Adleman invented the RSA algorithm, which could be used to produce primitive digital signatures (although only as a proof-of-concept—”plain” RSA signatures are not secure).[7] The first widely marketed software package to offer digital signature was Lotus Notes 1.0, released in 1989, which used the RSA algorithm.[citation needed]

To create RSA signature keys, generate an RSA key pair containing a modulus N that is the product of two large primes, along with integers e and d such that e d ≡ 1 (mod φ(N)), where φ is the Euler phi-function. The signer’s public key consists of N and e, and the signer’s secret key contains d.

To sign a message m, the signer computes σ ≡ md (mod N). To verify, the receiver checks that σe ≡ m (mod N).

As noted earlier, this basic scheme is not very secure. To prevent attacks, one can first apply a cryptographic hash function to the message m and then apply the RSA algorithm described above to the result. This approach can be proven secure in the so-called random oracle model[clarification needed].

Other digital signature schemes were soon developed after RSA, the earliest being Lamport signatures,[8] Merkle signatures (also known as “Merkle trees” or simply “Hash trees”),[9] and Rabin signatures.[10]

In 1988, Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Ronald Rivest became the first to rigorously define the security requirements of digital signature schemes.[11] They described a hierarchy of attack models for signature schemes, and also present the GMR signature scheme, the first that can be proven to prevent even an existential forgery against a chosen message attack.[11]

Most early signature schemes were of a similar type: they involve the use of a trapdoor permutation, such as the RSA function, or in the case of the Rabin signature scheme, computing square modulo composite n. A trapdoor permutation family is a family of permutations, specified by a parameter, that is easy to compute in the forward direction, but is difficult to compute in the reverse direction without already knowing the private key. However, for every parameter there is a “trapdoor” (private key) which when known, easily decrypts the message. Trapdoor permutations can be viewed as public-key encryption systems, where the parameter is the public key and the trapdoor is the secret key, and where encrypting corresponds to computing the forward direction of the permutation, while decrypting corresponds to the reverse direction. Trapdoor permutations can also be viewed as digital signature schemes, where computing the reverse direction with the secret key is thought of as signing, and computing the forward direction is done to verify signatures. Because of this correspondence, digital signatures are often described as based on public-key cryptosystems, where signing is equivalent to decryption and verification is equivalent to encryption, but this is not the only way digital signatures are computed.

Used directly, this type of signature scheme is vulnerable to a key-only existential forgery attack. To create a forgery, the attacker picks a random signature σ and uses the verification procedure to determine the message m corresponding to that signature.[12] In practice, however, this type of signature is not used directly, but rather, the message to be signed is first hashed to produce a short digest that is then signed. This forgery attack, then, only produces the hash function output that corresponds to σ, but not a message that leads to that value, which does not lead to an attack. In the random oracle model, this hash-and-decrypt form of signature is existentially unforgeable, even against a chosen-message attack.[6][clarification needed]

There are several reasons to sign such a hash (or message digest) instead of the whole document.

* For efficiency: The signature will be much shorter and thus save time since hashing is generally much faster than signing in practice.

* For compatibility: Messages are typically bit strings, but some signature schemes operate on other domains (such as, in the case of RSA, numbers modulo a composite number N). A hash function can be used to convert an arbitrary input into the proper format.

* For integrity: Without the hash function, the text “to be signed” may have to be split (separated) in blocks small enough for the signature scheme to act on them directly. However, the receiver of the signed blocks is not able to recognize if all the blocks are present and in the appropriate order.

Notions of security

In their foundational paper, Goldwasser, Micali, and Rivest lay out a hierarchy of attack models against digital signatures[11]:

1. In a key-only attack, the attacker is only given the public verification key.

2. In a known message attack, the attacker is given valid signatures for a variety of messages known by the attacker but not chosen by the attacker.

3. In an adaptive chosen message attack, the attacker first learns signatures on arbitrary messages of the attacker’s choice.

They also describe a hierarchy of attack results[11]:

1. A total break results in the recovery of the signing key.

2. A universal forgery attack results in the ability to forge signatures for any message.

3. A selective forgery attack results in a signature on a message of the adversary’s choice.

4. An existential forgery merely results in some valid message/signature pair not already known to the adversary.

The strongest notion of security, therefore, is security against existential forgery under an adaptive chosen message attack.

Uses of digital signatures

As organizations move away from paper documents with ink signatures or authenticity stamps, digital signatures can provide added assurances of the evidence to provenance, identity, and status of an electronic document as well as acknowledging informed consent and approval by a signatory. The United States Government Printing Office (GPO) publishes electronic versions of the budget, public and private laws, and congressional bills with digital signatures. Universities including Penn State, University of Chicago, and Stanford are publishing electronic student transcripts with digital signatures.

Below are some common reasons for applying a digital signature to communications:

Authentication

Although messages may often include information about the entity sending a message, that information may not be accurate. Digital signatures can be used to authenticate the source of messages. When ownership of a digital signature secret key is bound to a specific user, a valid signature shows that the message was sent by that user. The importance of high confidence in sender authenticity is especially obvious in a financial context. For example, suppose a bank’s branch office sends instructions to the central office requesting a change in the balance of an account. If the central office is not convinced that such a message is truly sent from an authorized source, acting on such a request could be a grave mistake.

Integrity

In many scenarios, the sender and receiver of a message may have a need for confidence that the message has not been altered during transmission. Although encryption hides the contents of a message, it may be possible to change an encrypted message without understanding it. (Some encryption algorithms, known as nonmalleable ones, prevent this, but others do not.) However, if a message is digitally signed, any change in the message after signature will invalidate the signature. Furthermore, there is no efficient way to modify a message and its signature to produce a new message with a valid signature, because this is still considered to be computationally infeasible by most cryptographic hash functions (see collision resistance).

Non-repudiation

Non-repudiation, or more specifically non-repudiation of origin, is an important aspect of digital signatures. By this property an entity that has signed some information cannot at a later time deny having signed it. Similarly, access to the public key only does not enable a fraudulent party to fake a valid signature. This is in contrast to symmetric systems, where both sender and receiver share the same secret key, and thus in a dispute a third party cannot determine which entity was the true source of the information.

Additional security precautions

Putting the private key on a smart card

All public key / private key cryptosystems depend entirely on keeping the private key secret. A private key can be stored on a user’s computer, and protected by a local password, but this has two disadvantages:

* the user can only sign documents on that particular computer

* the security of the private key depends entirely on the security of the computer

A more secure alternative is to store the private key on a smart card. Many smart cards are designed to be tamper-resistant (although some designs have been broken, notably by Ross Anderson and his students). In a typical digital signature implementation, the hash calculated from the document is sent to the smart card, whose CPU encrypts the hash using the stored private key of the user, and then returns the encrypted hash. Typically, a user must activate his smart card by entering a personal identification number or PIN code (thus providing two-factor authentication). It can be arranged that the private key never leaves the smart card, although this is not always implemented. If the smart card is stolen, the thief will still need the PIN code to generate a digital signature. This reduces the security of the scheme to that of the PIN system, although it still requires an attacker to possess the card. A mitigating factor is that private keys, if generated and stored on smart cards, are usually regarded as difficult to copy, and are assumed to exist in exactly one copy. Thus, the loss of the smart card may be detected by the owner and the corresponding certificate can be immediately revoked. Private keys that are protected by software only may be easier to copy, and such compromises are far more difficult to detect.

Using smart card readers with a separate keyboard

Entering a PIN code to activate the smart card commonly requires a numeric keypad. Some card readers have their own numeric keypad. This is safer than using a card reader integrated into a PC, and then entering the PIN using that computer’s keyboard. Readers with a numeric keypad are meant to circumvent the eavesdropping threat where the computer might be running a keystroke logger, potentially compromising the PIN code. Specialized card readers are also less vulnerable to tampering with their software or hardware and are often EAL3 certified.

Other smart card designs

Smart card design is an active field, and there are smart card schemes which are intended to avoid these particular problems, though so far with little security proofs.

Using digital signatures only with trusted applications

One of the main differences between a digital signature and a written signature is that the user does not “see” what he signs. The user application presents a hash code to be encrypted by the digital signing algorithm using the private key. An attacker who gains control of the user’s PC can possibly replace the user application with a foreign substitute, in effect replacing the user’s own communications with those of the attacker. This could allow a malicious application to trick a user into signing any document by displaying the user’s original on-screen, but presenting the attacker’s own documents to the signing application.

To protect against this scenario, an authentication system can be set up between the user’s application (word processor, email client, etc.) and the signing application. The general idea is to provide some means for both the user app and signing app to verify each other’s integrity. For example, the signing application may require all requests to come from digitally-signed binaries.

WYSIWYS

Main article: WYSIWYS

Technically speaking, a digital signature applies to a string of bits, whereas humans and applications “believe” that they sign the semantic interpretation of those bits. In order to be semantically interpreted the bit string must be transformed into a form that is meaningful for humans and applications, and this is done through a combination of hardware and software based processes on a computer system. The problem is that the semantic interpretation of bits can change as a function of the processes used to transform the bits into semantic content. It is relatively easy to change the interpretation of a digital document by implementing changes on the computer system where the document is being processed. From a semantic perspective this creates uncertainty about what exactly has been signed. WYSIWYS (What You See Is What You Sign) [13] means that the semantic interpretation of a signed message cannot be changed. In particular this also means that a message cannot contain hidden info that the signer is unaware of, and that can be revealed after the signature has been applied. WYSIWYS is a desirable property of digital signatures that is difficult to guarantee because of the increasing complexity of modern computer systems.

Digital signatures vs. ink on paper signatures

An ink signature can be easily replicated from one document to another by copying the image manually or digitally. Digital signatures cryptographically bind an electronic identity to an electronic document and the digital signature cannot be copied to another document. Paper contracts often have the ink signature block on the last page, and the previous pages may be replaced after a signature is applied. Digital signatures can be applied to an entire document, such that the digital signature on the last page will indicate tampering if any data on any of the pages have been altered.

Some digital signature algorithms

* RSA-based signature schemes, such as RSA-PSS

* DSA and its elliptic curve variant ECDSA

* ElGamal signature scheme as the predecessor to DSA, and variants Schnorr signature and Pointcheval-Stern signature algorithm

* Rabin signature algorithm

* Pairing-based schemes such as BLS

* Undeniable signatures

* Aggregate signature – a signature scheme that supports aggregation: Given n signatures on n messages from n users, it is possible to aggregate all these signatures into a single signature whose size is constant in the number of users. This single signature will convince the verifier that the n users did indeed sign the n original messages.

The current state of use — legal and practical

Digital signature schemes share basic prerequisites that— regardless of cryptographic theory or legal provision— they need to have meaning:

1. Quality algorithms

Some public-key algorithms are known to be insecure, practicable attacks against them having been discovered.

2.Quality implementations

An implementation of a good algorithm (or protocol) with mistake(s) will not work.

3. The private key must remain private

if it becomes known to any other party, that party can produce perfect digital signatures of anything whatsoever.

4. The public key owner must be verifiable

A public key associated with Bob actually came from Bob. This is commonly done using a public key infrastructure and the public key\leftrightarrowuser association is attested by the operator of the PKI (called a certificate authority). For ‘open’ PKIs in which anyone can request such an attestation (universally embodied in a cryptographically protected identity certificate), the possibility of mistaken attestation is non trivial. Commercial PKI operators have suffered several publicly known problems. Such mistakes could lead to falsely signed, and thus wrongly attributed, documents. ‘closed’ PKI systems are more expensive, but less easily subverted in this way.

5. Users (and their software) must carry out the signature protocol properly.

Only if all of these conditions are met will a digital signature actually be any evidence of who sent the message, and therefore of their assent to its contents. Legal enactment cannot change this reality of the existing engineering possibilities, though some such have not reflected this actuality.

Legislatures, being importuned by businesses expecting to profit from operating a PKI, or by the technological avant-garde advocating new solutions to old problems, have enacted statutes and/or regulations in many jurisdictions authorizing, endorsing, encouraging, or permitting digital signatures and providing for (or limiting) their legal effect. The first appears to have been in Utah in the United States, followed closely by the states Massachusetts and California. Other countries have also passed statutes or issued regulations in this area as well and the UN has had an active model law project for some time. These enactments (or proposed enactments) vary from place to place, have typically embodied expectations at variance (optimistically or pessimistically) with the state of the underlying cryptographic engineering, and have had the net effect of confusing potential users and specifiers, nearly all of whom are not cryptographically knowledgeable. Adoption of technical standards for digital signatures have lagged behind much of the legislation, delaying a more or less unified engineering position on interoperability, algorithm choice, key lengths, and so on what the engineering is attempting to provide.

Industry standards

Some industries have established common interoperabiltity standards for the use of digital signatures between members of the industry and with regulators. These include the Automotive Network Exchange for the automobile industry and the SAFE-BioPharma Association for the healthcare industry.

Using separate key pairs for signing and encryption

In several countries, a digital signature has a status somewhat like that of a traditional pen and paper signature, like in the EU digital signature legislation. Generally, these provisions mean that anything digitally signed legally binds the signer of the document to the terms therein. For that reason, it is often thought best to use separate key pairs for encrypting and signing. Using the encryption key pair, a person can engage in an encrypted conversation (e.g., regarding a real estate transaction), but the encryption does not legally sign every message he sends. Only when both parties come to an agreement do they sign a contract with their signing keys, and only then are they legally bound by the terms of a specific document. After signing, the document can be sent over the encrypted link. If a signing key is lost or compromised, it can be revoked to mitigate any future transactions. If an encryption key is lost, a backup or key escrow should be utilized to continue viewing encrypted content. Signing keys should never be backed up or escrowed.

Theo Wiki

Tư vấn công nghệ

[ẩn]* 1 Lịch sử

* 2 Tính pháp lý của chữ ký điện tử

o 2.1 Các định nghĩa pháp lý

o 2.2 Kiểm tra pháp lý đối với chữ ký điện tử

o 2.3 Pháp luật liên quan tới việc sử dụng chữ ký điện tử

* 3 Những sử dụng giả luật của chữ ký điện tử

* 4 Chữ ký mật mã

* 5 Tham khảo

* 6 Liên kết ngoài